News that a great white shark was tracked swimming in the Long Island Sound of New Jersey has been shared across the globe by multiple media outlets. Unfortunately, the actual location of the shark could be a little off.

![]()

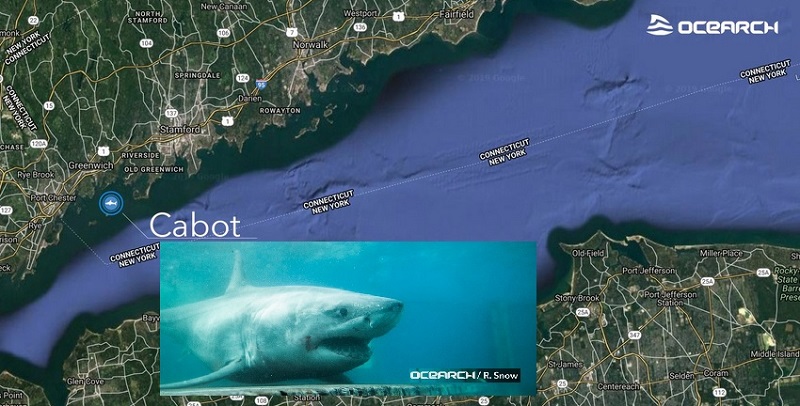

The location of the shark, named Cabot, has come into question. Cabot was tagged by the group OCEARCH in 2018 during an expedition to Nova Scotia. Expedition supporters in honor of Italian explorer John Cabot named the immature male shark.

Cabot has been incorrectly credited as the first shark to enter the sound. White shark Montauk has that honor since being tracked in the area in September 2016.

What separates the two sharks is size. Montauk was a young-of-the-year measuring roughly 60 inches shorter than the 9-foot-long Cabot. If Cabot did enter the sound, it would be the first large shark tracked in the area.

It is questionable that Cabot actually made it into the sound, and the first step to making a hypothesis is to understand how the data is obtained.

Sharks are tagged with Smart Position and Temperature Tags (SPOT). These tags, which are normally attached to the dorsal fin, use ocean water to complete a circuit inside the tag. Once the tag breaks the surface of the water and is “dry” for 30 seconds or more, a satellite signal is sent. Unfortunately the signal from the tag can sometimes become garbled, resulting in incorrect information.

Cabot was shown to be in Long Island Sound on May 20, but only a few hours later pinged on the opposite side of the sound. That would mean it made the almost 200-mile journey in about half a day, which would not be possible.

Several factors need to be accounted for when using SPOT tags. When the tag transmits data, a satellite needs to be near enough to receive the signal. The location of the satellite and the number of transmissions from the tag can impact the quality of a ping.

![]()

Two examples of this occurred in 2017 with great white, Mary Lee. In May of that year, the female shark pinged while heading inland on Nags Head, North Carolina. Then again on Nov. 16, her tracks appeared to show she had jumped over a landmass into Beasley Bay and then back into the ocean. OCEARCH confirmed both were bad pings.

While the shark tracker isn’t always 100% accurate, the system does give us an amazing new understanding of the movement of sharks. These predators help keep ocean life in balance and are vital to the underwater food chain.

In addition, the use of OCEARCH’s shark tracker has provided some important, but unfortunate news. In 2016, tiger shark Lexi’s spot tag was found onshore, leading to the general consensus that she was killed.

That same year, tiger shark Maroochy was captured and killed on a baited drum line in Australia. Mako shark Rizzilient was taken by fishermen in 2014 with the SPOT tag ending up in Portugal. The same year, Lampiao the tiger shark was killed and taken to Africa. Hammerhead Einstein met a similar fate, this time most likely at the hands of illegal fisherman who took the carcass into Mexico.

In the end, we can’t be completely sure if Cabot made it into Long Island Sound. However, there were a total of four pings in the Long Island Sound area, which leads credence to a bad ping being emitted on the south side of the area.

If Cabot did make it that deep into the area, it would be fascinating. Even if not, it would be equally interesting.

Twenty years ago, few people could have guessed that several hundred thousand people would be watching and speculating where sharks travel. With the continued tagging efforts of groups like OCEARCH, the data pool of shark tracks will continue to grow and we can gain a better understanding of sharks, as well as the overall health of our oceans.